baltakatei

/ˈbɑːltəkʊteɪ/. Knows some chemistry and piping stuff. TeXmacs user.

Website: reboil.com

Mastodon: baltakatei@twit.social

- 34 Posts

- 122 Comments

31·25 days ago

31·25 days agoGranted, but it is endless because it supplies itself with water from your blood.

You know she’s a competent teacher because she never loses her head.

Utah: Monticello (Italian, but locally pronounced “monta sell-oh”)

You’re telling me there is no Walla Walla, England?

2·1 month ago

2·1 month agoYo estaba pensando por qué no había “Share full article links” en los artículos. Pensaba que era un síntoma de que mi cuenta estaba registrada en los EE.UU.

4·1 month ago

4·1 month agoElves can live over a thousand years (one dark elf we know of is blessed by their evil deity and is over 5,000), but dwarves only about 2-400 years (I think?) and half lings about 100-150ish, humans standard 80.

After reading The Age of Em (2016) by Robin Hanson, I wish there were stories about races that went the other way, lifespan-wise: extremely small people who lived only 1 year, even smaller people who lived only 1 month, some very extremely small but very powerful ones that lived only a day, etc. The idea is that artificial people (emulated people, or Ems) could have subjectively similar characteristics and experiences to the larger physical entities (e.g. humans, but perhaps even dwarves, elves, and etc., since theyʼre just emulated minds), but their artificial emulated substrate allows their minds to develop and age orders of magnitude faster; they also could solve certain problems orders of magnitude faster but practical limitations on delays between thought and physical interactions (your mind would waste away if you had to wait a whole subjective hour between each physical step during a walk with a standard 1.5 meter body) require their bodies to be very small.

To ems that are smaller and faster, sunlight seems dimmer and shows more noticeable diffraction patterns. Magnets, waveguides, and electrostatic motors are less useful. Surface tension makes it harder to escape from water. Friction is more often an obstacle, lubrication is harder to achieve, and random thermal disruptions to the speed of objects become more noticeable. It becomes easier to dissipate excess body heat, but harder to insulate against nearby heat or cold (Haldane 1926; Drexler 1992).

A crude calculation using a simple conservative nano-computer design suggests that a matching faster-em brain might plausibly fit inside an android body 256 times smaller and faster than an ordinary human body (Hanson 1995).

Compared with ordinary humans, to a fast em with a small body the Earth seems much larger, and takes much longer to travel around. To a kilo-em, for example, the Earth’s surface area seems a million times larger, a subway ride that takes 15 minutes in real time takes 10 subjective days, an 8-hour plane ride takes a subjective year, and a 1-month flight to Mars takes a subjective century. Sending a radio signal to the planet Saturn and back takes a subjective 4 months. Even super-sonic missiles seem slow. However, over modest distances lasers and directed energy weapons continue to seem very fast to a kilo-em.

Call them speedlings, or some variant of sprite, but I think its an interesting world-building concept.

10·1 month ago

10·1 month agoOr authors could preëmptively declare their works to be in the public domain upon their death.

I wish Creative Commons had a license like that. Something like

CC PDD(Public-Domain-on-Death) which would activate upon the creator’s death, allowing them and publishers to freely monetize their work while they’re alive, but which would release the work into the public domain immediately after.It might even incentivize music and book publishers to get their artists health insurance. 😃

“Create a python script to count the number of

rcharacters are present in the stringstrawberry.”The number of 'r' characters in 'strawberry' is: 2

deleted by creator

1·1 month ago

1·1 month agodeleted by creator

2·1 month ago

2·1 month agoDe nada. Espero que puedan compartir algunos artículos del New York Times acá con los demás.

“That all life beyond this planet never existed, no matter how irrationally improbable that may be.”

81·2 months ago

81·2 months agoTime to rip off the bandage. https://linuxmint.com/ https://www.debian.org/

161·2 months ago

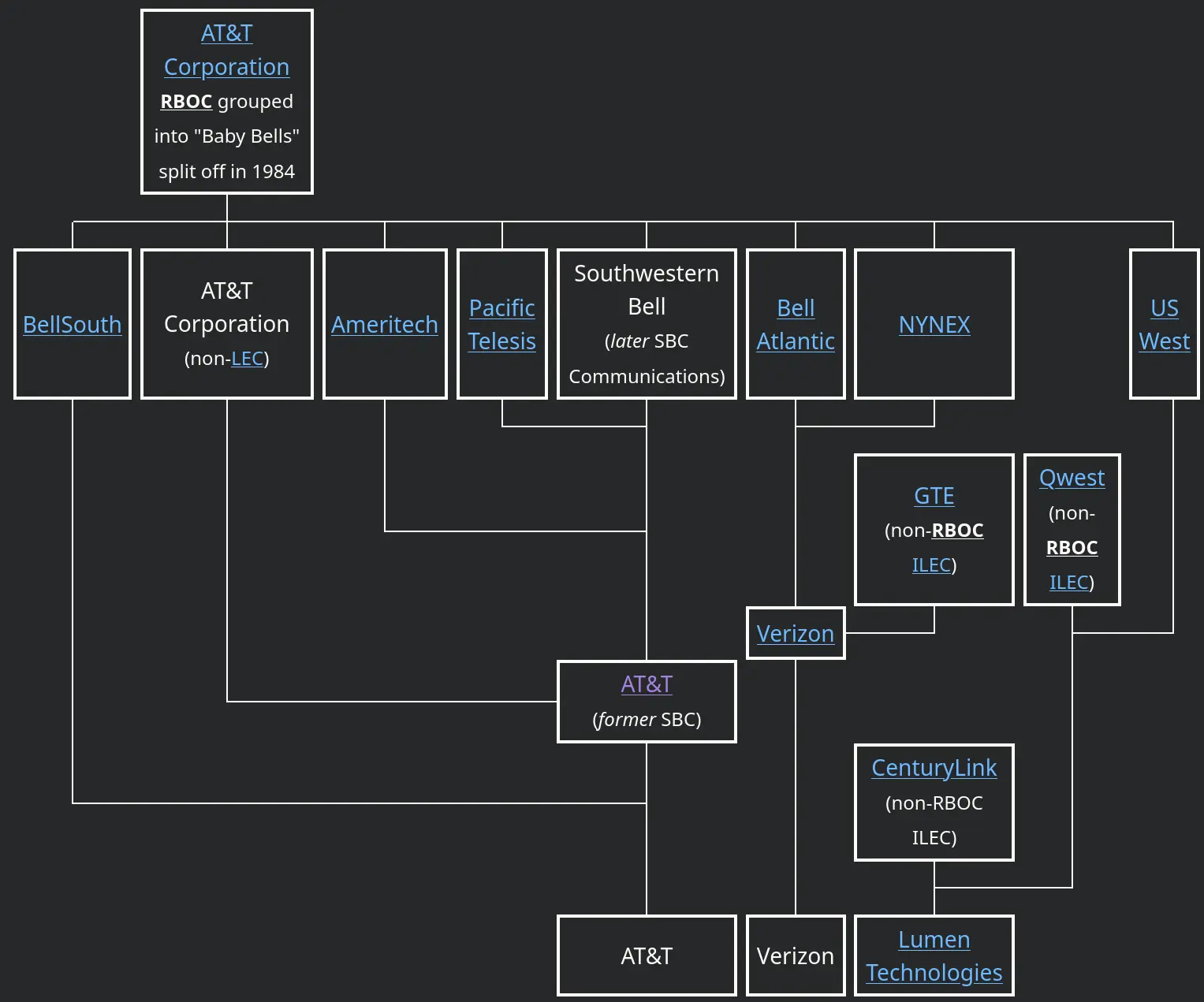

161·2 months agodon’t let them slowly re-consolidate in the following 20 years

I too remember how AT&T was broken up only for most of its Baby Bells to remerge back into Ma Bell.

To prevent this for future breakups, I say the content and services sold by big tech should be made competitively compatible and interoperable via nullification of DRM laws; people buy music and movies and cloud storage; let them legally move their purchases to any competitor and big tech companies will break up naturally as local competitors emerge from people who dislike big tech for their own reasons. Monopolies cannot be trusted to lower prices for content and services. Legally nullifying DRM is like the FCC telling customers in 1968 that it was finally okay to ignore the “Bell equipment only” legal warning that had kept them locked into leasing their telephone sets for usurious amounts from AT&T for decades. A few years later, in 1982, AT&T was broken up. AT&T is almost a total monopoly again, but phones remain interoperable.

Based on my cheatsheet, GNU Coreutils, sed, awk, ImageMagick, exiftool, jdupes, rsync, jq, par2, parallel, tar and xz utils are examples of commands that I frequently use but whose developers I don’t believe receive any significant cashflow despite the huge benefit they provide to software developers. The last one was basically taken over in by a nation-state hacking team until the subtle backdoor for OpenSSH was found in 2024-03 by some Microsoft guy not doing his assigned job.

3·2 months ago

3·2 months agoI can see why people of the future will look on early 21st century medicine as barely a step above blood-letting.

Can’t wait for the day when Uncle Sam to turns brown.

1·2 months ago

1·2 months agoHere is some background reading from Chokepoint Capitalism (2022) by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow. Specifically, it is from “Chapter 3: How News Got Broken”. I recreated the citations in the markdown as links and tool-tips.

spoiler

COOKIE MONSTERS

Ultimately, both Google and Facebook are ad companies, deriving about 80 percent and 98 percent (respectively) of their revenues from advertising. Between them, they control 70 percent of the US ad market, and more than 65 percent in the UK.4 They have sewn up the search and social ad markets in ways that let them extract ever more value—to the cost of the journalists, video makers, musicians, and other creative workers who provide the culture and information to which those ads get attached.

Google’s strategy for locking in suppliers like news publishers has been to vertically integrate throughout the ad chain. It now serves up the ads, buys ad space from publishers and sells it to others, provides the analytics that sites use to persuade advertisers to place content on them, and operates the search engine ad-supported sites rely on for traffic. An investigation by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority found that Google controlled the whole online ad market, controlling at least 50 percent and up to 100 percent at different points of the chain.5

Google provides at least a basic version of each of these services to businesses for free, which initially seemed like a boon but was actually a trap. Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo despairs of ever extracting his site. "Running TPM absent Google’s various services is almost unthinkable… . Some of them are critical and I wouldn’t know where to start for replacing them. In many cases, alternatives don’t exist because no business can get a footing with a product Google lets people use for free."6

Google makes the online market even more hostile to new entrants by putting some of its monopoly profits toward maintaining its dominance. It has bought its way to search default on every platform: device manufacturers (including Apple, LG, Motorola, and Samsung), wireless carriers (like AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon), and browser developers (such as Mozilla and Opera) all take money to deliver their users into Google’s maw. It pays billions each year to Apple alone. That enables Google to capture almost 90 percent of all general search engine queries and almost 95 percent on mobile devices. With Google providing the answers to almost every question we ask, it’s no wonder publishers despair of breaking free.

Dina Srinivasan researches the opaque online ad industry, after ten years working within it. She points out that Google dominates ad markets via conduct that would be illegal in other trading markets: "Google’s exchange shares superior trading information and speed with the Google-owned intermediaries, Google steers buy and sell orders to its exchange and websites (Search and YouTube), and Google abuses its access to inside information."7 This iron-fisted control gives Google a stalker’s view into publishers’ businesses. But it’s not the only one who gets to peek inside. The way Google has historically sold its ads gives that information away to huge numbers of others—and that’s been hugely damaging to news publishers too.

You probably already know that today’s internet is based on mass surveillance of you and everyone you know. Dossiers about your activity and preferences are constantly being compiled and updated, facilitated by cookies, the tiny data packets that identify and track you online. When you navigate to a web page, the ad server uses cookies to identify you, summons your dossier, correlates it with your identity across multiple databases, and offers brokers (sometimes dozens of them!) the opportunity to show you an ad. That’s how you end up with those creepy ads that follow you around the web after you carry out a search on, say, erectile dysfunction: you get a tag called “person interested in boners” and that attracts bids from boner-pill vendors.

All of that is reasonably well known. But what’s less well known, and just as important, is what happens to the losers of the real-time auctions when you visit a site. Say you visit the Washington Post. Dozens of brokers bid on the chance to advertise to you. All but one loses the auction. But every one of those losers gets to add a tag to its dossier about you: “Washington Post reader.” Advertising on the Washington Post is expensive. “Washington Post reader” is a valuable category: a lot of blue-chip firms will draw up marketing plans that say, “Make sure we tell Washington Post readers about this product!”

Here’s the thing: the companies want to advertise to Washington Post readers, but they don’t always care about advertising in the Washington Post. And now there are dozens of auction “losers” who can sell the right to advertise to you, as a Post reader, when you visit cheaper sites.

When you click through one of those dreadful “Here’s twenty-two reasons to put a rubber band on your hotel room’s door handle” websites, every one of those twenty-two pages can be sold to advertisers who want to reach Post readers, at a fraction of what the Post charges.

In other words, the ad auction system enables advertisers to buy the publication’s audience without contributing to the publication itself. Some brands, especially luxury brands, still value appearing in the prestige source—Chanel and Mercedes Benz want to be associated with the New York Times, not a tacky “twenty-two reasons” site. But not all advertisers care how they reach you. And so, to a large extent, this system disintermediated news publishers from the value of their creations.

That was a huge problem. News had long relied on an ad revenue model that itself relied on more profitable content to subsidize other important public interest work. As Clay Shirky says, in the print world "Walmart was willing to subsidize the Baghdad bureau. That wasn’t because of any deep link between advertising and reporting, nor was it about any real desire on the part of Walmart to have their marketing budget go to international correspondents. It was just an accident. Advertisers had little choice other than to have their money used that way, since they didn’t really have any other vehicle for display ads."8 Newspapers didn’t have to do much to capture ad revenue, since advertisers had little other choice.

The online world gave advertisers a range of new options, and brands (naturally!) took advantage of them. However, the consequence was that news publishers lost the premium that enabled them to invest in costly and vital content.

Although these changes cost news publishers extraordinary amounts, they generated rich rivers of gold for others. There’s almost no transparency in online ad markets, so nobody really knows how much money goes where, but huge sums are being gobbled up by ad-tech platforms like Google’s.

One known technique for maximizing profits is for Google to buy up ad space from publishers at a discounted rate and sell it on to advertisers for a huge and undisclosed premium. When the Guardian purchased some of its own ad inventory and followed the money, it discovered that up to 70 percent of revenues were siphoned off before ever reaching the publisher.9 Middlemen were snatching most of the value, leaving news providers with as little as 30 cents of each dollar spent on ads attached to their content. Back in 2003, by contrast, almost the full dollar went to the publishers.10

Online advertising is a seriously lucrative business. A 2020 report of the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority found that Google’s cost of capital was about 9 percent, on which it was earning supracompetitive returns of over 40 percent. Facebook, which has a similar playbook but focused on social media rather than search, had even higher returns—a ludicrous 50 percent.11 In a competitive market, publishers would sell their ads elsewhere. But the Google-Facebook duopoly gives them no such choice.

It is Kefkaʼs Tower, according to “Final Fantasy Ultimania Archive, Volume 1” (2018). Dark Horse Books. Page 259 of 335. ISBN: 978-1-50670-644-3. OCLC: 1043915833.