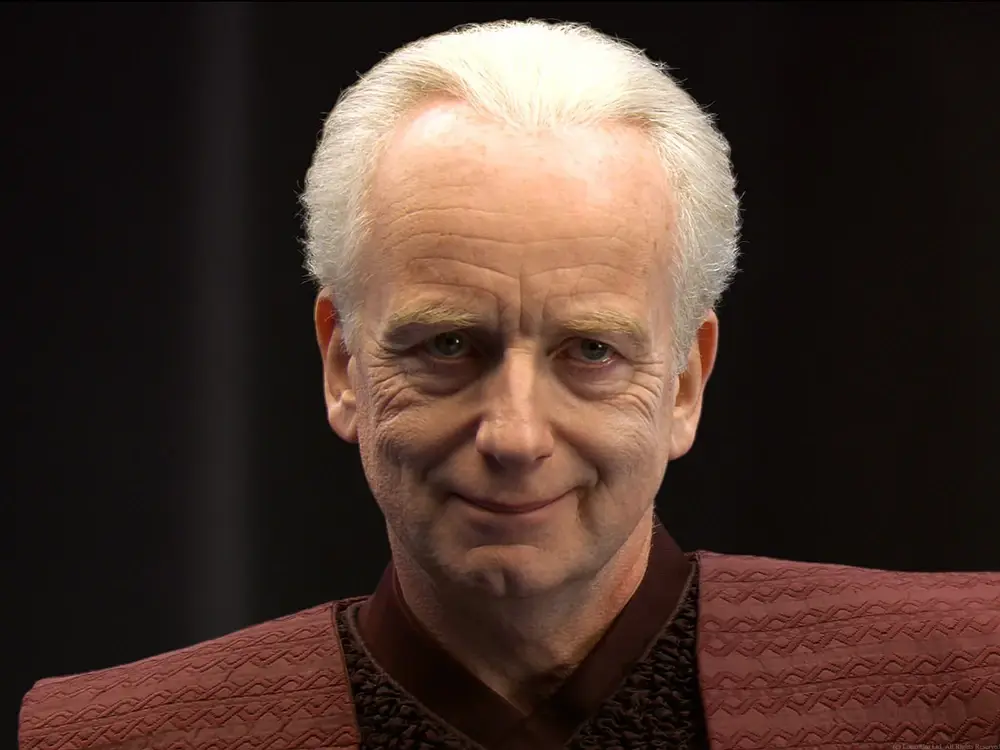

Looks like Palpatine:

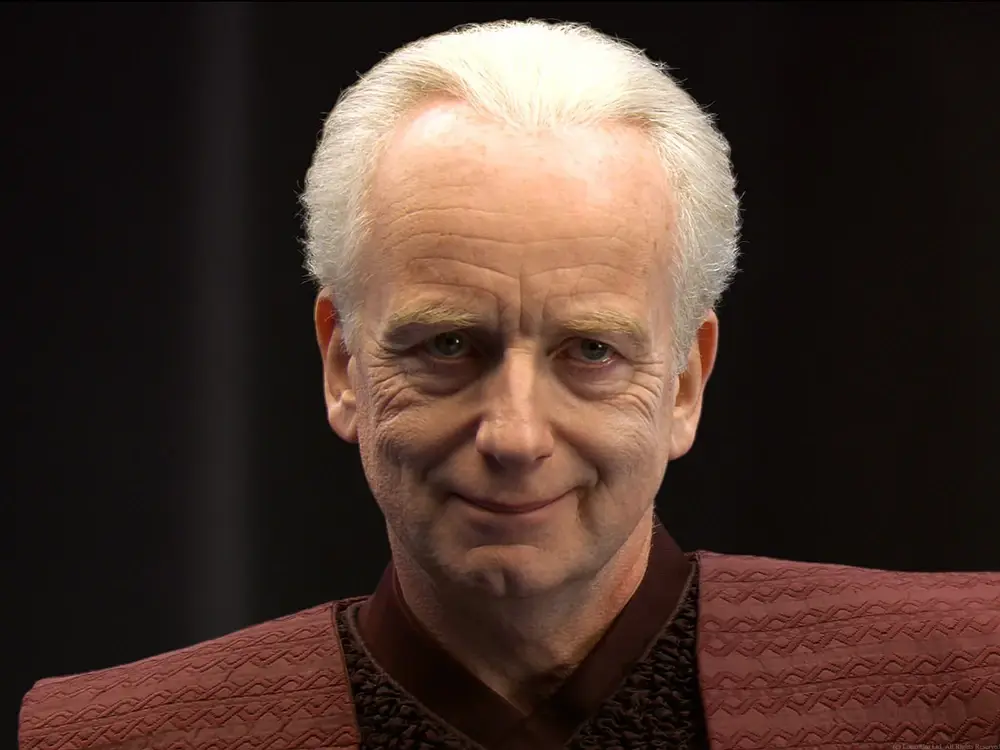

Looks like Palpatine:

Thought I’d finish the Monad Tutorial since I stopped midway…

The general notion that the abstraction actually captures is the notion of dependency, the idea that an instance x of your type can be in some common operation dependent on other instances of your type. This common operation is captured in bind. For Promises for example, the common operation is “resolving”. In my first post, for the getPostAuthorName promise to resolve, you first need to resolve getPost, and then you need to resolve getUser.

It also captures the idea that the set of dependencies of your x is not fixed, but can be dynamically extended based on the result of the operation on previous dependencies, e.g.:

const getPostAuthorName = async foo => {

const post = await getPost(foo)

if (post === undefined) return undefined

const user = await getUser(post.authorId)

return user.username

}

In this case, getPostAuthorName is not dependent on getUser if getPost already resolved to undefined. This naturally induces an extra order in your dependents. While some are independent and could theoretically be processed in parallel, the mere existence of others is dependent on each other and they cannot be processed in parallel. Thus the abstraction inherently induces a notion of sequentiality.

An even more general sister of Monad, Applicative, does away with this second notion of a dynamic set and requires the set of dependents to be fixed. This loses some programmer flexibility, but gains the ability to process all dependents in parallel.

The problem is people constantly try to explain it using some kind of real world comparison to make it easier to visualize (“it’s a value in a context”, “it encodes side effects”, “it’s a way to do I/O”, “it’s just flatmap”, “it’s a burrito”), when all it really is is an abstraction. A very, very general abstraction that still turns out to be really useful, which is why we gave it the cryptic name “monad” because it’s difficult to find a name for it that can be linked to something concrete simply because of how abstract it is. It really is just an interface with 2 key functions: (for a monad M)

- wrap: (x: T) => M[T] // wraps a value

- bind: (f: (y: T) => M[U], x: M[T]) => M[U] // unwraps the value in x, potentially doing something with it in the process, passes it to f which should return a wrapped value again somehow, and returns what f returns

Anything that you can possibly find a set of functions for that fits this interface and adheres to the rules described by someone else in this thread is a monad. And it’s useful because, just like any other abstraction, if you identify that this pattern can apply to your type M and you implement the interface, then suddenly a ton of operations that work for any monad will also work for your type. One example is the coroutine transformation (async/await) that is an extremely popular solution to the Node.JS “callback hell” problem that used to exist, and which we call do-notation in Haskell:

// instead of

const getPostAuthorName = foo => getPost(foo).then(post => getUser(post.authorId)).then(user => user.username)

// you can do this

const getPostAuthorName = async foo => {

const post = await getPost(foo)

const user = await getUser(post.authorId)

return user.username

}

This is a transformation you can actually do with any monad. In this case Promise.resolve is an implementation of wrap, and then is an implementation of bind (more or less, it slightly degenerate due to accepting unwrapped return values from f). Sadly it was not implemented generally in JS and they only implemented the transform specifically for Promises. It’s sad because many people say they hate monads because they’re complex, but then heap praise on Promises and async/await which is just one limited implementation of a monad. You may have noticed that generators with yield syntax are very similar to async/await. That’s because it’s the exact same transformation for another specific monad, namely generators. List comprehensions are another common implementation where this transform is useful:

// instead of

const results = []

for (const x of xs) {

for (const y of ys) {

results.push({ x, y })

}

}

// you could have

const results = do {

const x = yield xs

const y = yield ys

return wrap({ x, y })

}

Another (slightly broken) implementation of monads and the coroutine transform people use without knowing it is “hooks” in the React framework (though they refuse to admit it in order to not confuse beginners).

Fuck… I actually just wanted to write a short reply to the parent comment and devolved into writing a Monad Tutorial…

I’m not sure what kind of point you’re trying to make here. Obviously every wildfire ultimately originates from an ignition source, be that a human made fire, some glass focusing the sunlight, a cigarette or whatever other source you can think of. They don’t spawn into existence.

Drought caused by extreme heat makes it much easier for these small fires to spread into an actual wildfire though. It’s not mutually exclusive.

It’s a direct consequence of matchmaking (and in League of Legends specifically also of terrible game design). If you were to play with the same, smaller set of people every time this behavior wouldn’t happen as often because people would simply start telling you you’re a dick. In matchmaking there are no consequences as the chance you’ll ever play the same opponent again before they forgot about you is minimal.